The enduring legacy of America’s oldest Black publishers

The tragedy at Third World Press has shed light on how precarious the situation is for many Black publishers across the U.S.

When a burst pipe flooded the basement of Third World Press, an independent Black-owned publishing company on the South Side of Chicago, Haki Madhubuti was devastated.

“Our losses were tremendous,” said Madhubuti, a renowned educator and poet who founded Third World Press in 1967. “We had a dumpster about the size of a small kitchen, and we eventually filled up two dumpsters. That was about 65, 70 percent of our inventory. It hurt badly.”

The water flooded the basement, ruining a significant amount of the store’s backlist, or collection of older books. Computers, bookshelves, and furniture were also damaged. Thousands of books now sit in a dumpster behind the building. The damage amounted to over $200,000, Madhubuti estimated. Destroyed inventory included works from Black literary giants like Amiri Baraka, Gwendolyn Brooks, John Henrik Clarke, Sonia Sanchez, and more.

A fundraiser was created to support the publisher. Third World Press exceeded its goal of $95,000, thanks to more than 500 donations — including a $50,000 contribution from Brooklyn Nets point guard Kyrie Irving.

Madhubuti, 81, said he was not familiar with GoFundMe before the flooding but was heartened by the responses. Well-wishers not only responded by donation online, but with notes and letters. He said people even came to the building to personally deliver cash and checks. Third World Press has been in the community for over 50 years, and the community showed up for them when they needed help most. “It’s been a movement to keep us alive.”

The fundraiser will remain active until the end of February.

Although the publisher was able to meet its goal, the tragedy at Third World Press shed light on how precarious the situation is for many Black publishers across the country. Black legacy publishers, or Black publishers founded by those who lived through the civil rights era, simply don’t have the resources to handle devastating losses.

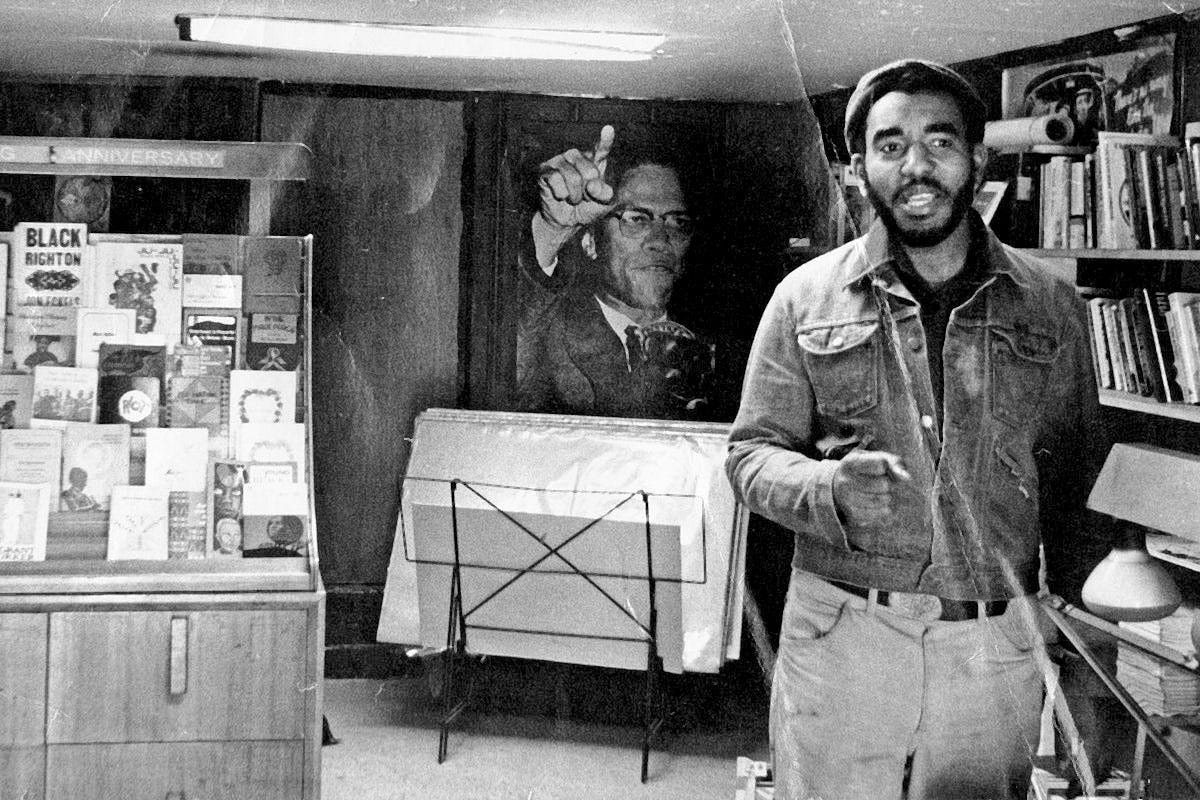

Third World Press is the oldest independent Black publishing company in the country still operating today (Madhubuti says it is the oldest in the world). It is the publishing home of Gwendolyn Brooks, the first Black author to win the Pulitzer Prize, poets Sterling Plumpp and Margaret Walker, and many others.

Madhubuti is widely regarded as a pioneer of the Black Arts Movement, alongside its founder Amiri Baraka, and other literary icons like Nikki Giovanni, Audre Lorde, and more. Third World Press is one of the few major legacy Black publishers still in existence, including Baltimore’s Black Classic Press, New Jersey’s Just Us Books, and “sister presses” Africa World Press and The Red Sea Press, two affiliated imprints in New Jersey as well. There’s also Detroit’s Broadside Lotus Press, born of a merger between two legacy publishers.

The 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s saw a major increase in the number of Black bookstores and publishers, but many faced tremendous difficulty finding the resources to stay afloat. But they remained committed to publishing Black-centered literature by any means necessary.

“They published what they truly felt Black people need to read,” said Char Adams, a reporter with NBC BLK and author of the forthcoming book Black-Owned: The Revolutionary Life of the Black Bookstore. “When the founders of Black-owned presses said, ‘Okay, we are going to prioritize meaningful work over profit,’ they resigned themselves to not being these super massive money makers.”

Many of the commercial Black publishers from that era have ceased operation. Today, there are at least 100 Black-owned publishers in the United States, according to the African American Literature Book Club. But it is difficult to define what a Black publisher is exactly, and the data is scant.

A representative from Publishers Weekly said there is no definitive list of Black publishers in the U.S. and sent over their annual salary and jobs survey, which showed the racial makeup of the publishing industry is still overwhelmingly white.

Paul Coates, founder of Black Classic Press, agreed that it’s difficult to define what a Black publisher is today. There are self-publishers, Black publishers sponsored by white publishers, and online publishers.

“In the past, when you said Black publisher, there were a lot, but they didn’t necessarily have the same commitment legacy publishers had. But I can tell you how legacy Black publishers survive because our tracks are parallel,” explained Coates, and if his last name looks familiar, you may know his son, Ta-Nehisi. “And that is to say, each of them are still struggling. We struggle to get titles out. We struggle to promote the titles.”

After heading up the Baltimore chapter of the Black Panther Party in the 1960s and 1970s, Coates formed a prison literacy program run through a Black bookstore. The program was met with much pressure from federal and state officials, and several years later, in 1978, he founded Black Classic Press.

“What you’ll find consistent with all of the legacy publishers is that they all came out of different organizations and different struggles,” Coates said of the Black legacy publishers. “All of the people who founded those presses came out of struggling organizations. They came out of organizations that declared the interest of the Black community to be its highest order.”

Decades later, these companies still depend on one another for survival. Black Classic Press also operates BCP Digital Printing, the only Black book printing company in the country, and will help Madhubuti reprint many of the books he lost.

Black legacy publishers are lifelines that connect us to the Black intellectual thought of generations past — lifelines more vital than ever as state and federal officials work to block Black studies and thought. We stand to lose more than books if these publishers were to disappear.

Third World Press is in the process of repair. It will take some time to replace the books, furniture, and computers, but Madhubuti isn’t worried. He sees the future of Third World Press to be inextricably linked with the future of Black people.

“We only function at one level as long as Black people are functioning. If Black people do well and continue to grow and develop, we are going to do well and continue to grow and develop,” Madhubuti said.

“Why? Because the mission is to be an arm of literacy for our people and others.”

Phil, thanks for bringing attention to this important subject. You and your readers may be interested in a panel discussion I'll be moderating at IBPA's Publishing University, "The Legends of Independent Black Publishing" https://aalbc.com/tc/topic/10045-publishing-university-the-legends-of-independent-black-publishing/ The publishers of Third World Press, Africa World Press and The Red Sea Press, and Just Us Books will be in on a panel discussion I'll be moderating.

thank you for this! i came across the article but didn’t feel the immense pain that came with the loss of so much black literature.