Inside the battle to preserve African American studies in Florida

Floridians resist Gov. Ron DeSantis’s attempts to erase African American studies.

On the first day of Black History Month, the College Board announced it overhauled its Advanced Placement course in African American studies, a high school class that allows students to earn college credit. The nonprofit organization stripped prominent Black writers and academics known for their work in Black feminism, critical race theory and queer thought from the curriculum.

In January, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said his administration was going to ban the course from the state’s schools, claiming it “significantly lacks educational value” and that it violated the Stop WOKE Act—legislation he signed into law last year restricting race and gender-related curriculum in schools. Republicans and other right-wing politicians quickly supported it.

“We proudly require the teaching of African American history. We do not accept woke indoctrination masquerading as education,” Florida Education Commissioner Manny Diaz Jr. wrote on Twitter when the ban was announced.

Although the governor claimed victory after the College Board released the new curriculum, the organization said in a statement that the major revisions were “substantially complete” by Dec. 22, 2022, several weeks before the governor and his administration banned the course.

The College Board further explained that it had not purged “Black feminism” and the “gay experience” from the course. But there are some significant differences between what appeared in the draft version and what is now part of the new version. Many progressive topics—like reparations, abolition, intersectionality and the queer experience, for example—have either been minimized or dropped from the 234-page document as a requirement for instructors teaching the class.

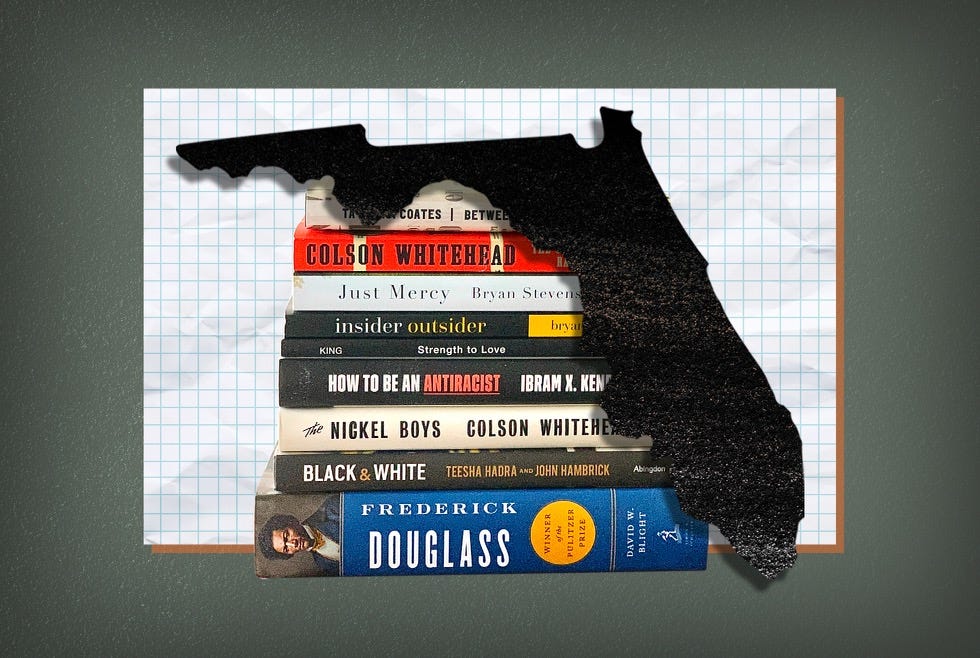

Black literary and academic figures like Alice Walker, Angela Davis, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Sylvia Wynter, Nikki Giovanni, Amiri Baraka and more have also been removed from the new curriculum. Read it for yourself; you can access the pilot document here.

Critics see the updated curriculum as a blatant attempt to suppress African American studies in schools. Whether the changes were at the behest of DeSantis or not, there has been a surging right-wing effort to ban critical race theory in schools nationwide, despite school officials and educators denying they even teach the academic framework. Florida’s Department of Education may not have directly influenced the College Board, but the subjects removed from the AP African American studies curriculum appear to suggest it has been taking some cues from the culture war the GOP is waging.

And DeSantis has been crystal clear about his attempts to whitewash the state of Florida, recently touting his plans to defund diversity, equity and inclusion programs at every single Florida university.

“Everybody knows that what he’s doing is unfair. He’s blocking kids, white or Black, from learning more about African American history,” said a history teacher in Palm Beach County who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retaliation. “You’re defeating the purpose of education. If students want to learn, whether you agree or disagree with it, that’s prohibiting our goal, which is to teach.”

Floridians aren’t idly watching. Some have decided to take matters into their own hands to prevent DeSantis’s creeping authoritarianism and ensure students are able to learn all aspects of Black history — not just what the governor deems appropriate.

After DeSantis announced he would ban AP African American studies in Florida’s schools, Pastor Andy Oliver felt it was essential that his church, Allendale United Methodist in St. Petersburg, Florida, open up its space to partner with educators willing to teach students the course.

These instructors are taking a big risk by teaching. “DeSantis could make life difficult for them,” said Oliver, explaining that the governor has a history of being “petty and punitive” toward those who defy him. “The environment in Florida right now is just very scary because that’s how he has governed, by creating a culture of fear.”

The educators working at the church reached out to The College Board and their course will be available for credit, Oliver said. And “because it’s banned, it’s super popular now. So shoutout to the governor for making this class popular,” he said.

Oliver, a white man who has been the pastor at Allendale United Methodist for seven years, explained that offering the space is a step in helping to repair the harm his church has done in the past as it moves into the future. He credited several influential Black women throughout his education, including Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons and Angela Cowser, with shaping him into a community organizer.

The way Oliver sees it, DeSantis’s policies are a direct attack on the community he loves. “When the governor said that this class was of little educational value, he sent the message to Black children that they are of little value,” he said. “And I believe that by stepping in and doing this class, we are sending a different message: that these children are of immeasurable value.”

Related: The Meaning Of African American Studies

Some Floridians saw the assault on African American studies coming well ahead of the governor’s ban. Several Florida-based branches of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), an organization dedicated to studying the lives of African Americans, started working on creating Freedom Schools for youth in the wake of the George Floyd murder.

During the civil rights movement of the 1960s, members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee developed Freedom Schools, an education program that aimed to address the basic educational needs of disenfranchised Black youth and push them to become politically engaged citizens. These ran as a six-week summer program in places like Mississippi, where schools were still essentially segregated, despite the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision.

Today, Freedom Schools aren’t only summer literacy programs — they can provide Black students with an opportunity to learn about their history and culture outside a school district’s curriculum.

David Wilkins, president of the Manatee-Sarasota branch of ASALH, explained that all six branches in Florida are working together to create Freedom Schools. The St. Petersburg branch of ASALH hopes to have its school up and running by spring. Wilkins said the pilot program for his chapter will start on Feb. 18.

“The mission of ASALH is to promote, preserve research, interpret and disseminate information about Black life and history to the global community,” said Wilkins, a lawyer and historian. “So what the governor’s done is obviously a direct affront to our mission. That’s why we’re doing what we’re doing and looking for other things we can do.”

Other alternatives to the AP course exist as well. Marvin Dunn, a professor emeritus at Miami’s Florida International University, is taking high school students across the state so they can see exactly where some of the worst atrocities toward Black people occurred for themselves. That way, no one can suppress it.

Dunn heads his “Teach the Truth” tours, which take dozens of students to historic areas in Florida where whites committed acts of racial terror and lynchings.

On the tour, students will visit Newberry, a small city where several Black Floridians, including a pregnant woman, were lynched by a white mob in 1916. They will also go to Rosewood, a once thriving rural Black town that was burned to the ground and decimated by an insatiable white mob in 1923.

He has also pursued legal action over the state law, as he is one of several plaintiffs involved in a lawsuit against DeSantis’s Stop WOKE Act. “Listen, if there is such a thing as the woke mob in Florida, I aspire to lead it,” Dunn told The Washington Post.

Related: A Black professor defies DeSantis law restricting lessons on race, The Washington Post

The AP African American studies ban didn’t directly affect elementary students, but educators are nervous it only sets the stage for further restrictions. For them, this fight is about a broader battle to keep African American studies alive in Florida, and teachers are finding ways to resist, however small it may seem.

According to an instructional leader at a public school in Orange County, who spoke on condition of anonymity, some teachers have started putting books about African American history on display just so their students have access to it, in protest of an unclear Florida law requiring the approval of books in classroom libraries from a state-trained librarian.

“Now that this is happening, teachers are trying to provide students with as much as they can. We’ve been doing research projects. We’re doing a spirit week for Black history,” the teacher said of their elementary school. “We’re just trying to teach Black history as much as possible.”

Tina Certain, chair of the Alachua County School Board, was “troubled” by the governor’s ban on AP African American studies but wants people to be outraged that teachers are barely following the original law that mandates African American history is taught in schools.

“African American studies should be not just taught like a one-off,” said Certain, who encourages teachers to use all the resources available. “It should be infused, meaning that it should be woven throughout all of the curriculum from kindergarten through 12th grade. I think that’s where the focus should be.”

“DeSantis is using culture wars to distract people from the larger issue. And I don’t think we should take that.”

Excellent article with wonderful hyperlinked info. I will be sharing widely!