The Negro Motorist Green Book exhibit makes its way to the DC Public Library

The guide, created by postman Victor Green, gave Black Americans safe spots to eat and rest as they traveled across the United States during the era of Jim Crow.

For Taylor, the thought of needing a book to travel safely within her own country is unimaginable.

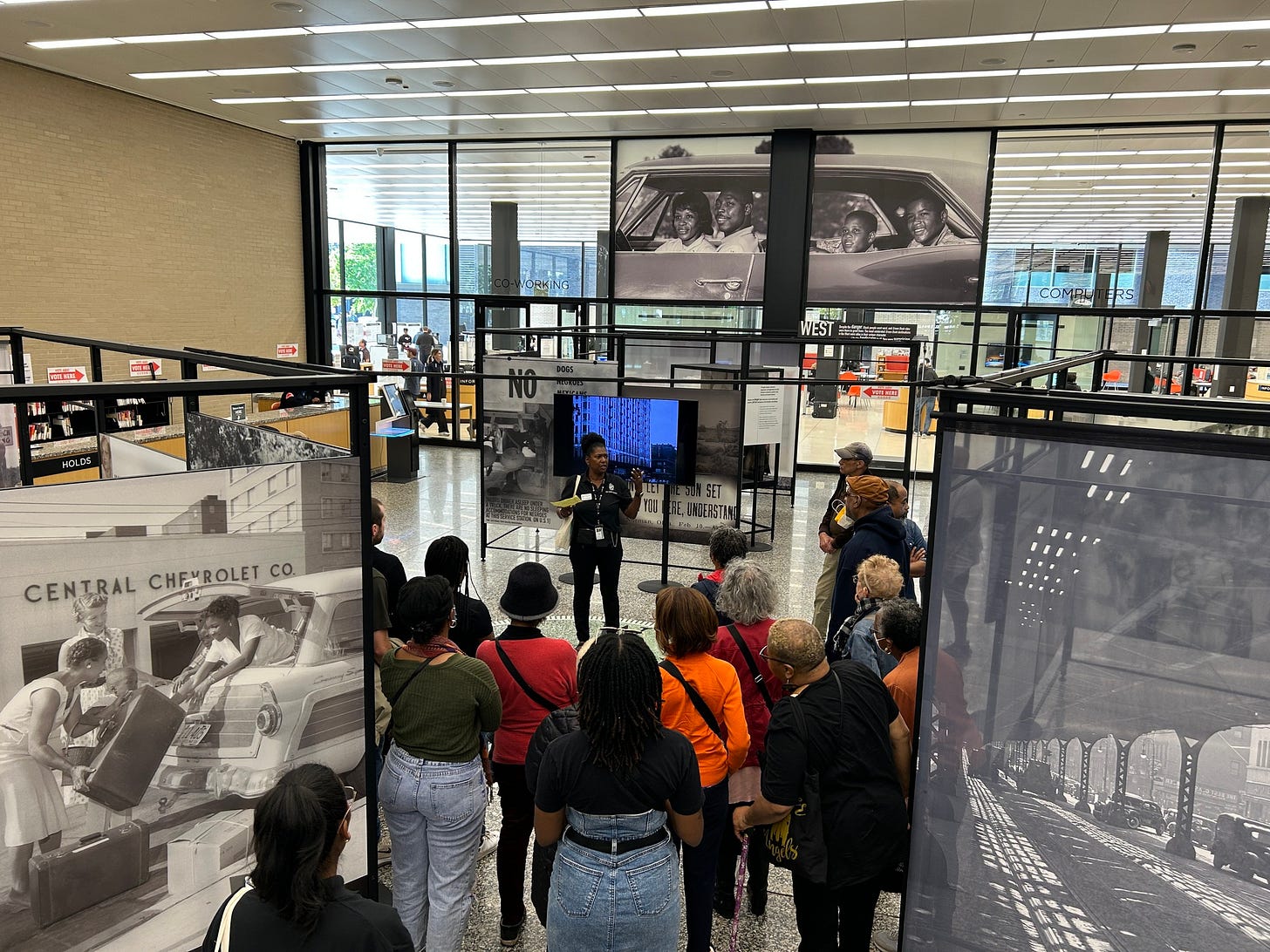

The 19-year-old from Oxon Hill, Maryland, was with her mother when she happened upon "The Negro Motorist Green Book: Lighting the Way Where the Way is Dark” exhibit at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, D.C. The pair were at the library for a separate event when the exhibition, which fills nearly the entire lobby with large displays, captivating photos and historic artifacts, caught their eye.

Trenece Fluelling, Taylor’s mother, said she had never heard of the guide despite being an avid reader. “I had never even heard of the Green Book before,” she said. “I want to learn more about it.”

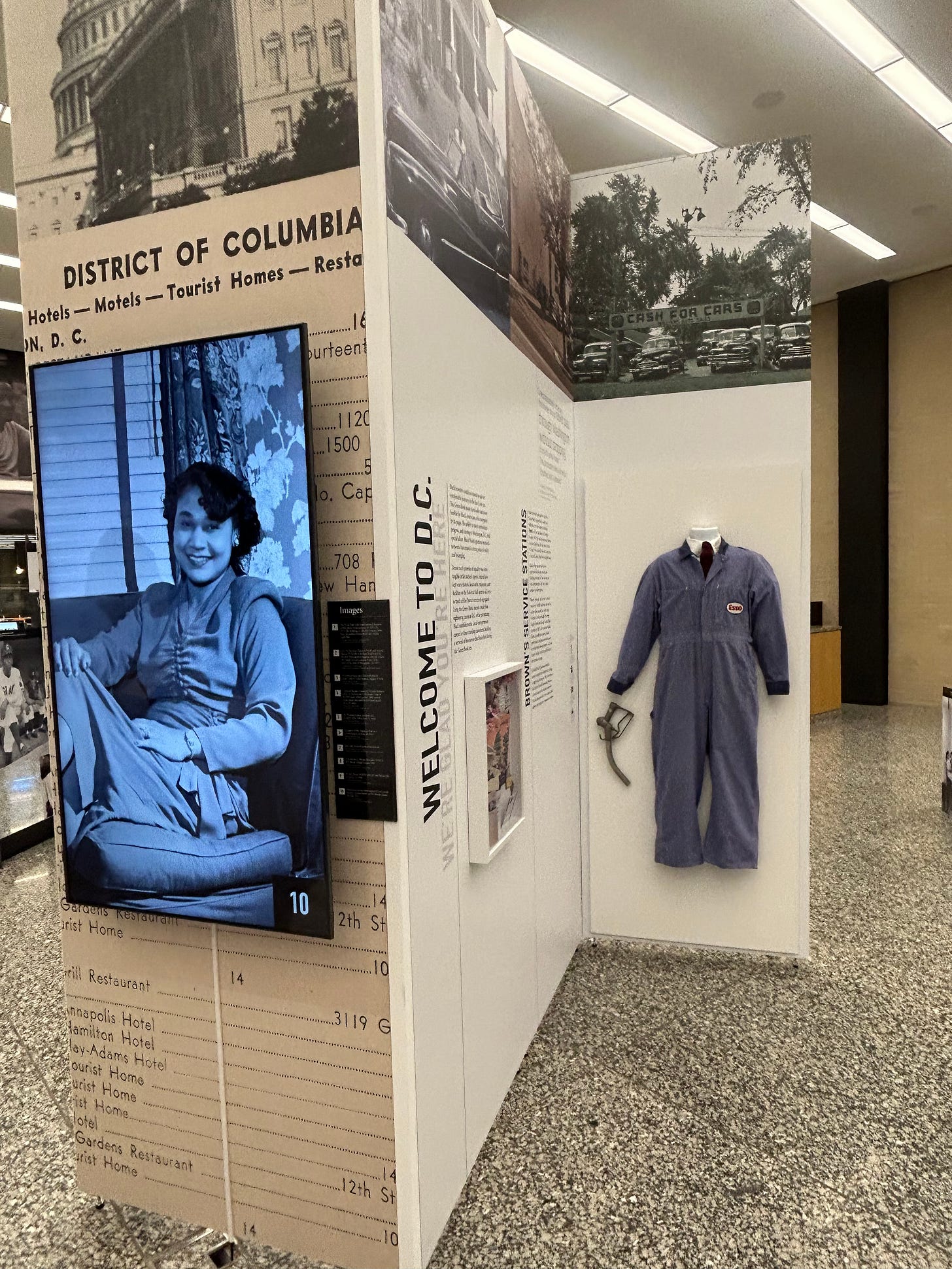

Curated by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service and documentarian Candacy Taylor, the exhibit tells the story of The Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide that provided Black Americans with safe spots to eat and rest as they traveled across the United States during Jim Crow. The book was created in 1936 by postman Victor Green, who was frustrated with the rampant discrimination and racism Black travelers faced on the road. Running out of fuel in Alabama or an stopping at unfriendly restaurant in Ohio could be a fatal mistake in the segregation era.

"The Green Book provided African Americans the means to navigate a dangerous and discriminatory world," said Richard Reyes-Gavilan, executive director of the DC Public Library. "This exhibition shows how a single publication could empower people to travel with dignity and find community across the nation.”

Visitors can read ledgers, flyers and first-hand accounts from Black travelers who relied on the book. They can also sit behind the wheel of a vehicle headed South and make decisions on what they should bring. When Taylor chose an empty can, a woman on screen explained that the can was necessary to use for long trips — it could be too dangerous to make a restroom stop.

(Video: Trenece Fluelling, Taylor’s mother, packs the trunk in the interactive)

The exhibit also highlights the many businesses and organizations that were friendly to Black patrons in the District of Columbia, like the Whitelaw Hotel in the U Street Corridor, which hosted jazz icons like Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington and other celebrities at the time.

The exhibition “weaves the Green Book's story into the District's history, giving visitors a chance to gain a deeper understanding of how people have long used ingenuity, solidarity and information to face racism,” Reyes-Gavilan continued.

Looking at the photos on display of the families traveling together despite the circumstances, Taylor said she “couldn’t believe” that the Green Book was once necessary. This, however, was Victor Green’s dream — the Green Book was never meant to be a permanent resource.

For Green, a future where Taylor never needed his guide was the future he looked toward. “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published,” the 1948 edition of the guide read.

The exhibit will be on display at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library until March 2025. Visitors can sign up for a guided tour on Wednesdays and Saturdays. A virtual component is also available for those who can’t make it to the capital.

It is so important that we flesh out all of the African American story. And why we must safeguard it from people—other Americans namely—who try to deny, dilute or claim it.

Our library system in DC is so cool!