Inside Colorado’s famous resort for Black Americans

Colorado was once a beacon for members of the Harlem Renaissance and Black families from all over the country.

By Erin O’Toole, High Country News

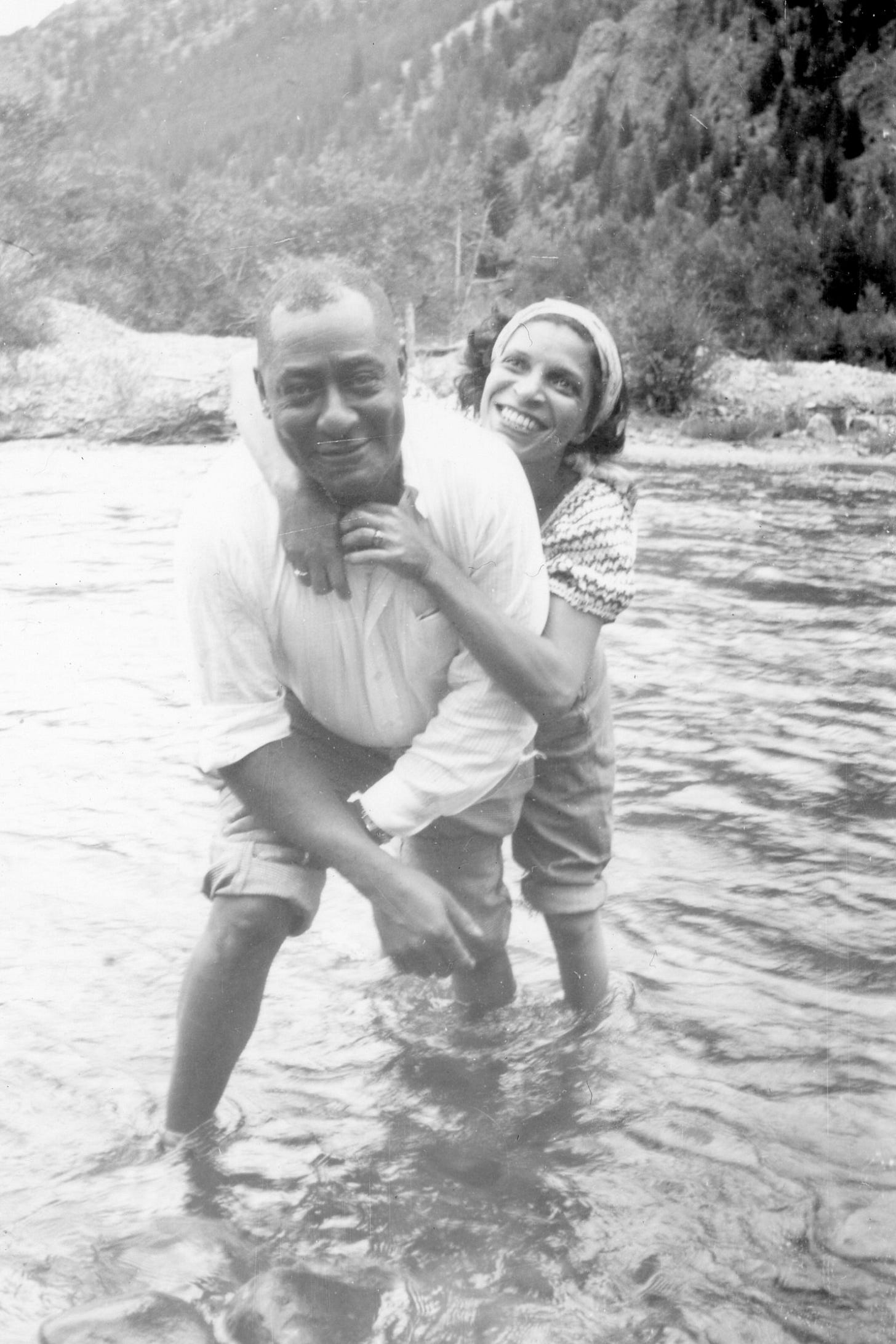

Summer heat has many people dreaming about escaping to the cool air of the high elevations. Tourists have traveled to mountain states for more than a century. But for Black Americans in the 1920s and 30s, segregation and discrimination severely restricted where they could travel and vacation – and Colorado came to be an important destination.

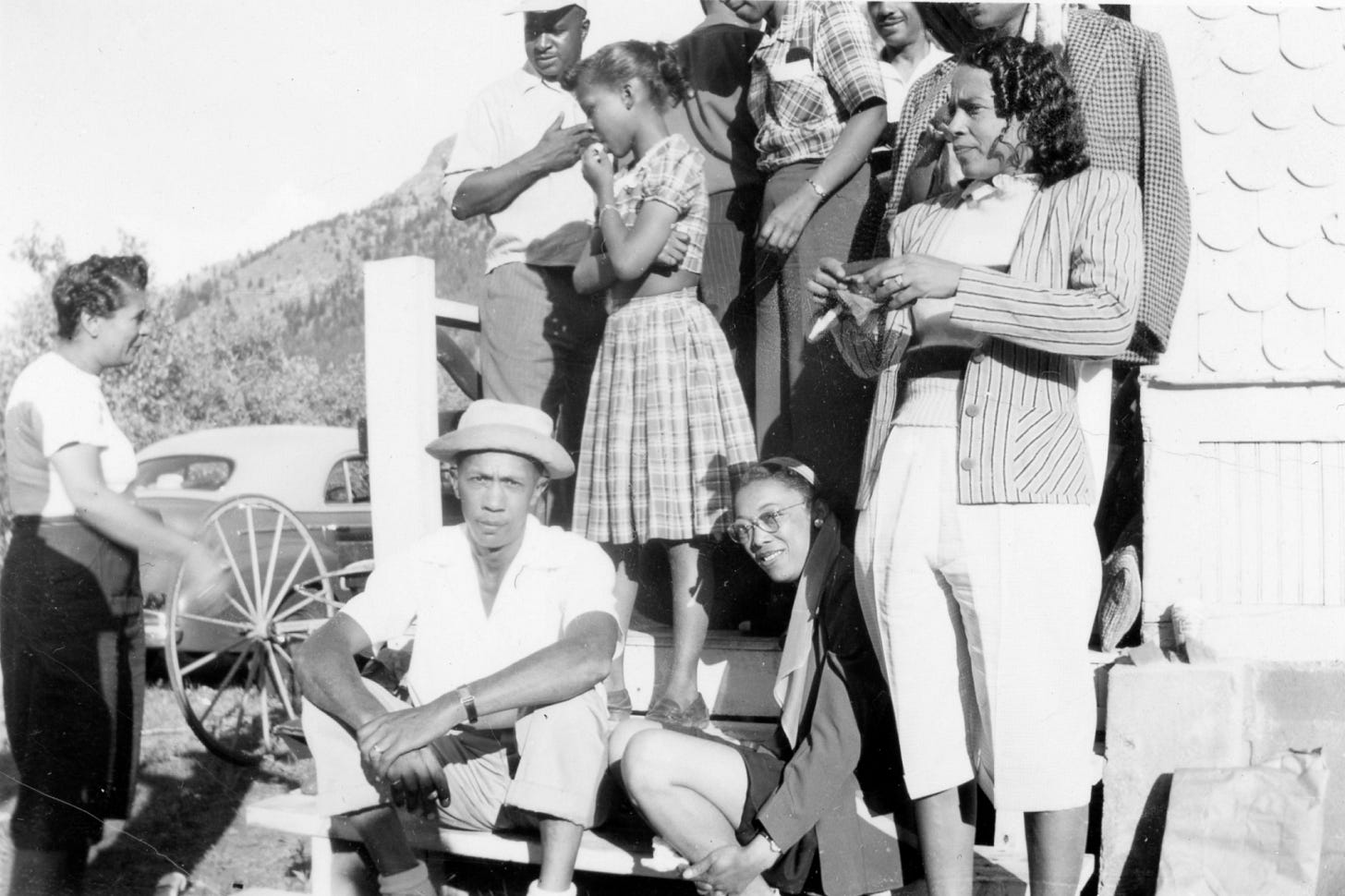

In 1922, Lincoln Hills was founded by and for African Americans near Rollinsville, northwest of Denver. It was the largest such resort west of the Mississippi River and drew visitors from all over the country. Tucked into a valley along South Boulder Creek, it offered a rare opportunity for Black Americans to feel safe in the outdoors. Families could buy lots for $50 to $100, and gathered there over the years.

History Colorado, which runs the state archives and museums, recently unveiled a new exhibit about Lincoln Hills. Erin O’Toole, a producer with High Country News partner KUNC, talked with Acoma Gaither, who helped curate the exhibit, about what memories she unearthed and why the resort is significant now. A version of this interview previously appeared on KUNC’s podcast In the NoCo; it appears here with edits for clarity and length.

Erin O’Toole: I know for some Black families in Colorado, owning a property at Lincoln Hills was almost like a family heirloom. What did owning a cabin there represent for Black individuals and families?

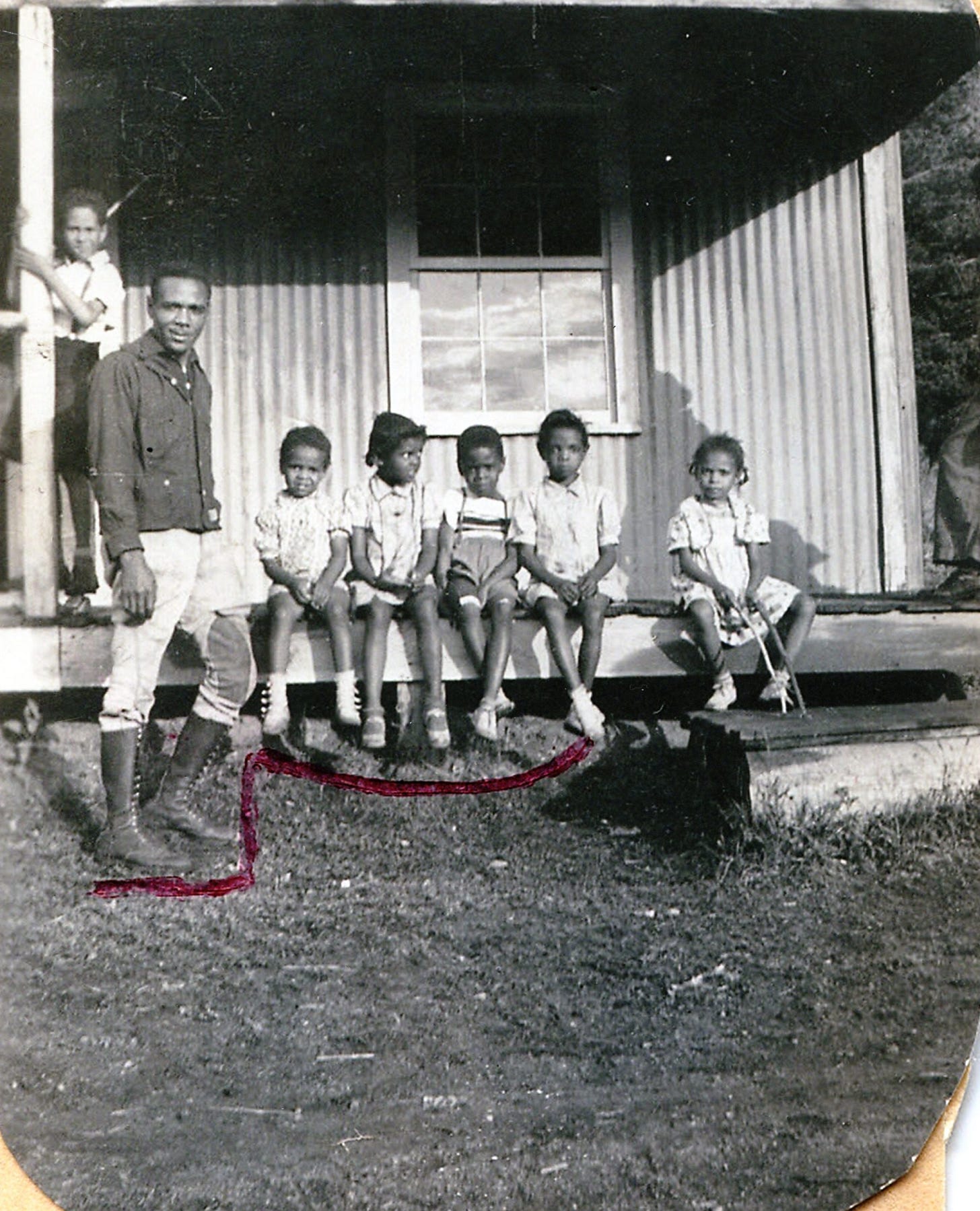

Acoma Gaither: Yeah, it was a powerful symbol of freedom and pride. This was a time of rampant housing discrimination and redlining. So, it was a symbol of legacy for Black families in Colorado. It also served as a multi-generational space. So, you had grandkids there, grandparents there. It really held this rich family history, you know, within the cabins. And I’ve heard from Judge Gary Jackson, who still owns his great-grandfather’s cabin there, that it’s a little slice of the American Dream for his family.

EO: So, would people build cabins on those lots?

AG: Yeah, some families built cabins. Some would just pitch tents.

I should mention that it wasn’t just Black Coloradans that went there. There were Black families from all over the country that came to Lincoln Hills.

EO: Lincoln Hills was created in the early 1920s during the time of segregation, Jim Crow laws, sundown towns, the Ku Klux Klan had a very strong presence in Colorado at that time. How did Lincoln Hills manage to exist outside of that environment?

AG: When we think about segregation, a lot of people think about water fountains or busses and lunch counters. But segregation really extended far beyond the built environment and into nature and the great outdoors. So, in Colorado, they didn’t have formal Jim Crow laws, but they had a lot of discriminatory policies and just plain intimidation for Black families in recreational spaces like public parks and swimming pools and campgrounds.

I was able to find meeting minutes from 1922 from National Park Service Park superintendents meeting where they said in quote, “We cannot openly discriminate against African Americans, but they should be told that the parks have no facilities for taking care of them.” So this was kind of a sentiment a lot of Black families felt when going to recreate, even in Estes Park. So that’s why Lincoln Hills was so necessary.

EO: What is your favorite artifact in the History Colorado exhibit?

AG: I looked through some of the photographs that were taken there, and that was kind of my roadmap to figuring out what did people wear. So I looked through our collection to find a 1940s ensemble of Western outdoor wear. That’s pretty much one of my favorite things that’s on display. We also have a wool bathing suit that some of the girls at the camp would wear too, that’s also on display.

EO: Was that common to have bathing suits made of wool?

AG: Yes! Seems a little cold.

EO: Lincoln Hills, as you mentioned, drew people from all over Colorado and all over the country. It also drew visitors that were some prominent African American writers, activists, musicians like Duke Ellington. Were they there to perform or give talks, or were they just there to relax and get some fresh mountain air?

AG: I believe they were there to just relax. A lot of the jazz musicians that came there actually would perform in Denver at different jazz venues like the Rossonian in Five Points. And then they would make their way to Lincoln Hills to relax. A lot of Harlem Renaissance writers came, like Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Countee Cullen and W.E.B. DuBois came, and they would actually hold literary salons there during their visits.

EO: Lincoln Hill sort of petered out as a community in the 1960s. What caused that?

AG: Outdoor spaces gradually became more welcoming for Black families through the 60s and 70s, and a big reason for that was the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which banned discriminatory laws keeping African Americans from buying homes or enjoying public lands. This brought a new wave of visitorship for places that were barred for black families in the past.

EO: How do you talk about the legacy of Lincoln Hills today?

AG: The legacy of Lincoln Hills is both a local Coloradan treasure, but also a part of the national story. And I think it really invites us to think about, you know, historically, who has access to leisure and land in the outdoors in America, and it really pushes you to think about equity in the outdoors today, like who feels welcome in nature now, and who has access to land and heritage spaces like this one. I think it pushes us to think about a more inclusive outdoor future, so everybody can see themselves reflected in Colorado’s mountains and open skies and just the surrounding environment.

KUNC’s Brad Turner contributed editing.

This story was originally published at High Country News and is republished here by permission.

I didn't just read this, I truly experienced it. You've taken Lincoln Hills from the shadows and put it back into the center of American history. That is important. Many of us grew up feeling excluded from natural spaces, as if nature wasn't for us. But this story reminded me that we have always found ways to enjoy, connect, and feel free, even when society told us we couldn’t.

Lincoln Hills’ legacy is a strong reminder that Black families have always valued land, community, and happiness. We have always created our own sanctuaries. Winks Lodge, the jazz greats, the literary gatherings—they are our treasures, our heritage.

This story pushes for meaningful discussions about land access, fairness in leisure, and who still feels unsafe outdoors. Thank you for bringing this story to light with care, context, and respect. I'm going to share this widely.

Very Cool !!