A talk with Paul Coates

I spoke with Paul Coates, founder of Baltimore's Black Classic Press, about his life, Black publishing, and his hopes for the future.

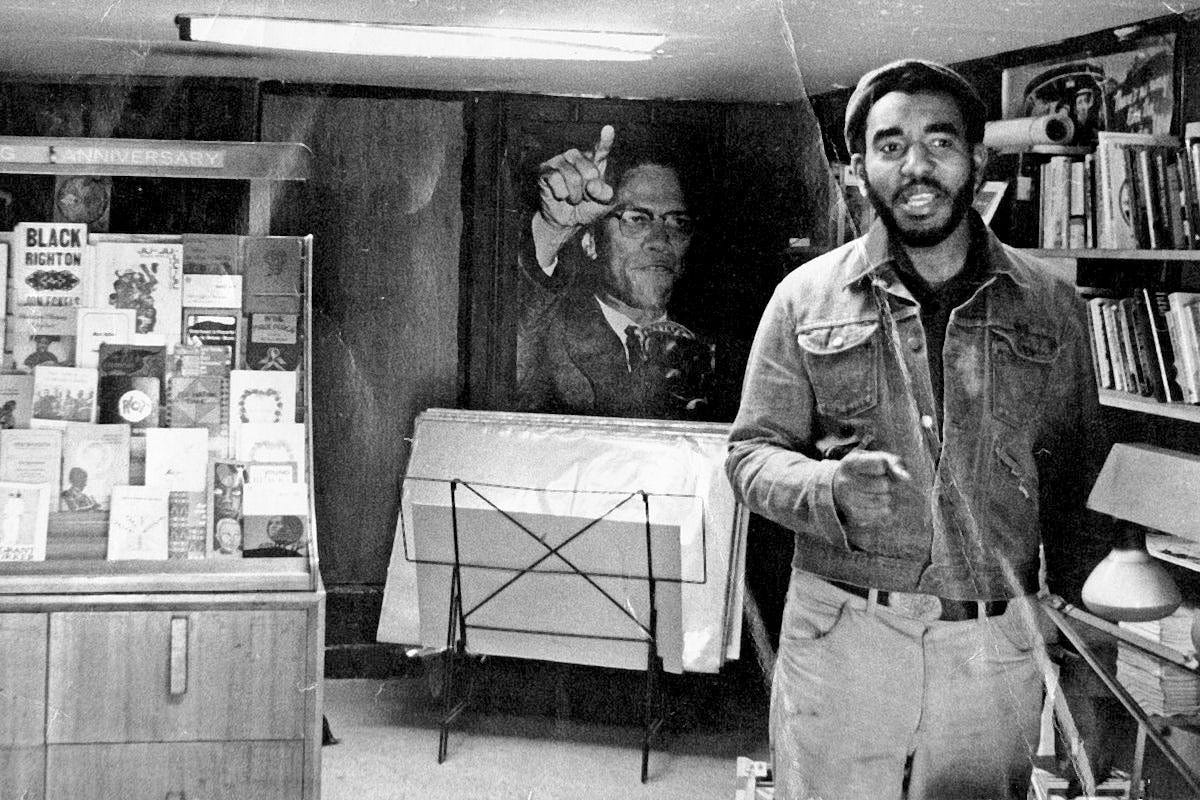

It’s not often that you get to speak with a history-maker. I interviewed Paul Coates, founder of the Black Classic Press in Baltimore, for my previous story about America’s oldest Black publishers.

He is the father of Ta-Nehisi Coates, a writer whose literary works have shaped much of the country’s discussions around race over the last decade. However, Paul Coates’s own story is worthy of retelling on its own: a Vietnam veteran, a former Black Panther, and a book publisher.

I spoke with Paul about his life, his work in Black publishing, and his hopes for the future.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Can you take me back to the ‘70s, when you founded Black Classic Press?

I came out of the Black Panther Party, and coming out of the party, I still wanted to advocate and be engaged with the struggle. And books provided that opportunity to do it. Coming out of the Panther Party, I had comrades that were still in jail under heavy charges, so they were gonna be there for a while.

Working with those comrades, we organized brothers in jail, and we developed a program for having them educated and be self-educated through books that we would send to the jail. And it was our intention to one day publish and print the books. We would send in these positive books, and we would get back positive returning citizens who would rebuild the black community. Well, that didn't happen so much. In fact, the book exchange came under quite a bit of pressure from the feds and the state.

We really didn't know how much pressure there was at that time, but we just knew they were blocking our moves. So we closed that down, and what we had been using was a Black bookstore as a base, which was founded to facilitate all of this. The bookstore continued according to plan.

About six years later, I'd set up Black Classic Press as the publishing arm. But that was supposed to be from the beginning. One part would be a bookstore, another part would be a publishing house, and another part would be a book printer. All of that was designed to be related. And it did happen. The publishing company started in 1978. It would take me until 1995 to set up the printing company. And so right now, the printing company is the only Black book printer in the country.

Can you describe the mission? Who were you trying to reach?

Our first audience were brothers who were incarcerated. And our intent was to expand on the experience of Malcolm X, expand on the experience of George Jackson. And that was by feeding the nation. We expected that many of the people who were incarcerated would come out of jail as new men. The whole idea of the bookstore was so that we had a vehicle that could obtain books and get books into the jail, as well as make information available in our community.

The feeling was at that time that both communities were oppressed. You had the community behind the wall that was oppressed, and you had the community that showed up on the larger side of the wall that was oppressed. And I felt that information was a factor — an important factor in terms of changing the level of oppression inside the jail and the level of oppression in our community.

Legacy Black publishers aren’t known for publishing books that are massive moneymakers, but that seems to be the point. Was that your mindset going into it?

I think you'd find that consistent with all of the legacy publishers. All of those publishers came out of different organizations and different struggles, and when I say all of them, you're really talking about four that have survived. They're Third World Press, Black Classic Press, Africa World Press, and Just Us Press. All of the people who founded those presses came out of struggling organizations. They came out of organizations that declared the interest of the Black community to be its highest order.

What are your thoughts on the state of Black publishers today?

That’s a hard thing. In the past, when you said Black publishers, there were a lot of Black publishers, but they didn't have the same commitment that the legacy publishers had. Today, it's the same thing. You’ve got a lot of Black publishers who are self-publishers, who are independent publishers, and you have Black publishers who are actually sponsored by white publishers. So, what we call a black publisher today … it was hard to define in the past, but it's even harder today. Almost anyone can be a publisher today.

I can tell you something about the legacy publisher. I can tell you something about them, how they survive and how they're doing because our tracks are parallel. Each of them is still struggling. Each of them still struggles to get titles out. We struggle to promote the titles. We are not anti-large or white corporate publishing, but there is something about white corporate publishing that is not inside of what we do. Being driven by money is ok for people who like that. But if you are talking about producing information that you feel to be critical, your whole reason for doing it is different. You're on a completely different side, and you're not on that side because you're making money off the books. You're on that side because you actually believe in this stuff that is in those books, or at least, you believe people have the right to write them.

What do you think of the future of Black voices with regard to our histories and stories? Are we in a dire place right now?

I don't think so. We [Black publishers] are threatened, but as a people, we are threatened, you see. I don't think that puts us in a dire place. We're probably in one of the best places we've ever been in. Some of the old activists were book printers. Frederick Douglas was a book printer. He was a printer, and he printed books. Martin Delany was a printer. They were publishers and printers. But when you leave that tradition, you find a lot of people who are publishing newspapers, and they're activists.

But all of that goes back. Even though I told you we struggle every day, the fact of the matter is we've struggled every day for 45 years. That says something. And I don't think it speaks to the end. I think it opens the door for successors, and it becomes a beginning. There's a platform now. Who do we find that step up and take over the platform? That becomes a question.

What about the future of Black publishing at large?

I think the future looks good. It hinges on … when I say it looks good, I'm talking about today and tomorrow. Anything beyond that it's gonna hinge on who the successors are. Do we have a young generation of people ready to step up and say, ‘I want to do that,’ you know? ‘I want to do that. I want to continue that legacy.’

A lot of it depends on that — where these young people are and how they'll step forward and how they'll make themselves known.